Object Oriented Design

Overview

Get a brief overview of the object-oriented design problems in this course along with its targeted audience and prerequisites.

We'll cover the following

What is object-oriented design?

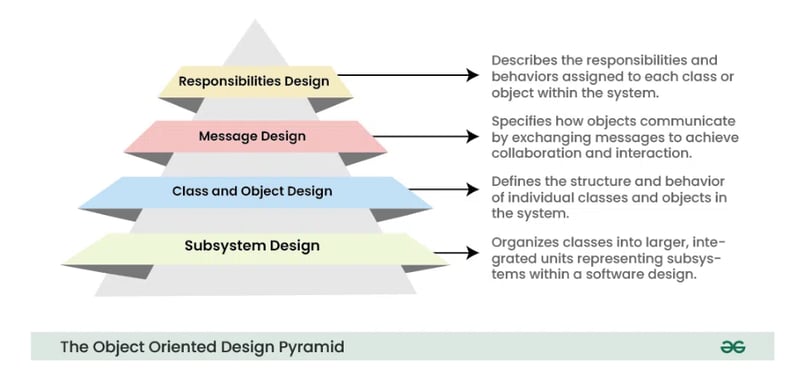

Object-oriented design (OOD) uses the object-oriented methodology to design a computational problem and its solution. It allows the application of a solution, based on the concepts of objects and models. OOD works as a component of the object-oriented programming (OOP) lifecycle. While designing a software solution, it is necessary to have less software development time and high code accuracy. OOD helps achieve this, since the design process involves objects communicating with each other and displaying the behavior of a program.

A typical object-oriented design (OOD) is hard. You never know what design problem you’ll be asked, and there are so many of them. Moreover, we expect you to design a near-perfect solution to the given problem that covers all the edge cases.

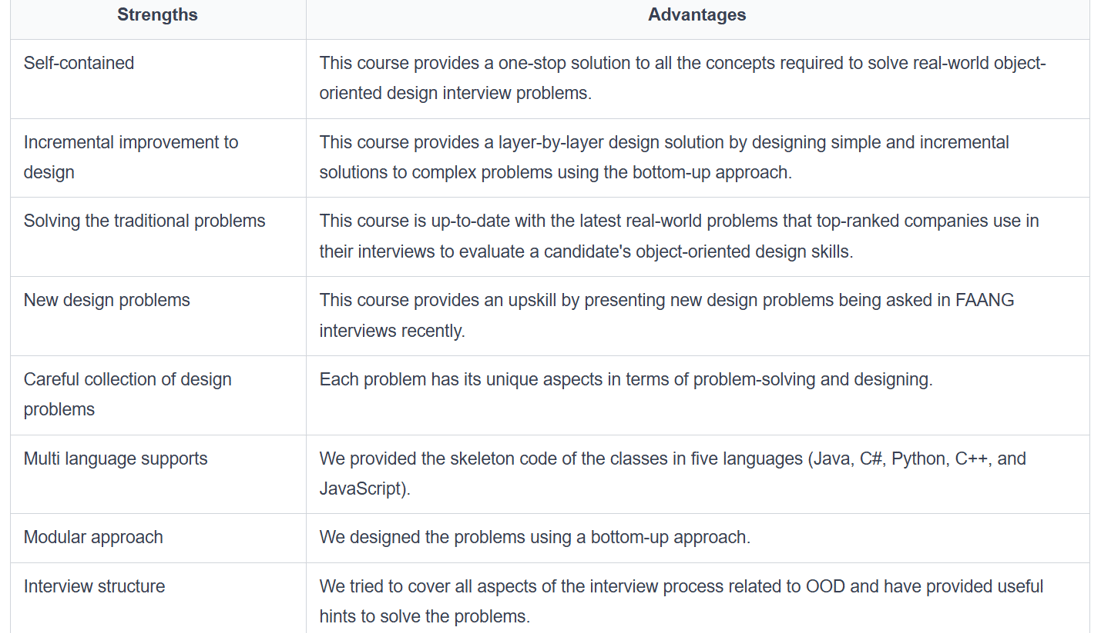

This course is about getting familiar with the fundamentals of object-oriented design with an extensive set of real-world problems usually asked in an object-oriented design (OOD) interview.

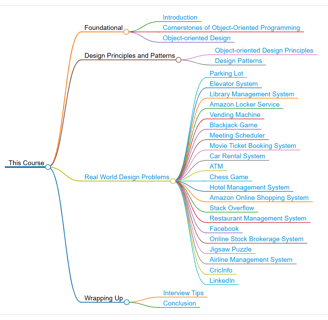

We’ll start with the introduction of the cornerstones of object-oriented programming and object-oriented design with an overview of different types of UML diagrams. We will also review a well-known object-oriented design principle, SOLID, followed by the definition and explanation of some of the most widely used design patterns. We’ll also illustrate 21 real-world design problems.

The purpose of providing foundational knowledge about object-oriented programming, object-oriented design, design principles, and design patterns before diving deep into the actual design problems is to equip our learners with the essential conceptual foundation. This is so that they don't get lost while designing a problem.

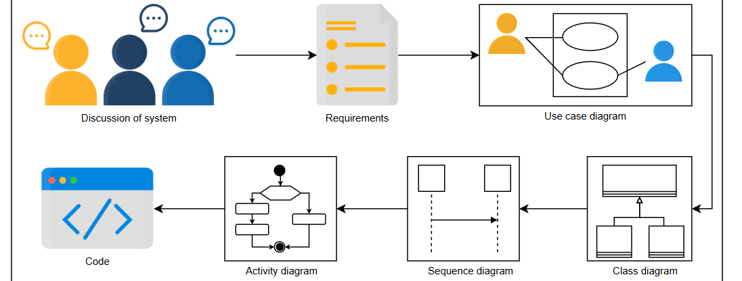

In each design problem, we have presented a detailed discussion of the problem requirements. We’ve modeled the findings with the help of use cases, as well as class, sequence, and activity diagrams for each problem.

The sequence of our discussion on each design problem

This consists of 28 sessions. These can be segmented into the four sections listed below:

Foundational: The foundational section is composed of three chapters. The first chapter introduces the course and its key features. The second chapter talks about object-oriented programming and its four paradigms. The third chapter introduces UML notations, and in this chapter, we focus on four widely used UML diagrams in object-oriented design.

Design patterns: There are two chapters in the design patterns section. The first chapter introduces the five design principles widely used in object-oriented software development called SOLID. The second chapter discusses the three design patterns: creational, structural, and behavioral.

Real-world design problems: There are twenty-one chapters in this section. The first chapter explains a typical object-oriented design interview process. In particular, this chapter discusses the steps involved in solving a design problem. Chapters 6–27 describe and solve the 21 real-world design problems in detail. We have dedicated a chapter for each problem in which we walk the learner through all the phases of designing an object-oriented problem. These chapters include requirement gathering, use case diagrams, class designs, sequence and activity diagrams, as well as the skeleton code implementation in five popular languages.

Wrapping up: This section provides interview tips for the reader and wraps up this course.

Note: Although we did our best to keep the sessions independent, our readers will find it useful to read them in the sequence provided below.

Object Oriented Programming:

We use programming to solve real-world problems, and it won't make sense if one can't model real-world scenarios using programming languages. This is where Object Oriented Programming comes into play. It's a programming model that is independent of the concept of Objects and concepts.

OOP is a programming style, not a tool. This programming style involves dividing the program into pieces of objects which can communicate with each other. Each Object has it's own unique set of properties. These properties later accessed and modified through the use of various operations.

Building Blocks Of OOPS:

Class and Objects

Attributes

Methods

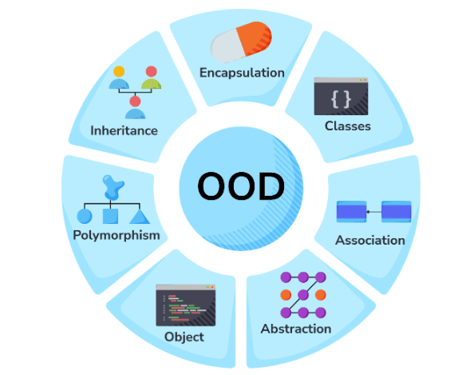

4 Basic Principles of OOPS:

There are 4 major principles that make a language Object Oriented. These are Encapsulation, Data Abstraction, Polymorphism, and Inheritance. These are also called as four pillars of Object-Oriented Programming.

Encapsulation

Encapsulation is the mechanism of hiding of data implementation by restricting access to public methods. Instance variables and methods are kept private and only accessor methods are made public to achieve this.

Say we have a program. It has a few logically different objects that communicate with each other — according to the rules defined in the program.

Encapsulation is achieved when each object keeps its state private, inside a class. Other objects don’t have direct access to this state. Instead, they can only call a list of public functions — called methods.

So, the object manages its own state via methods — and no other class can touch it unless explicitly allowed. If you want to communicate with the object, you should use the methods provided. But (by default), you can’t change the state.

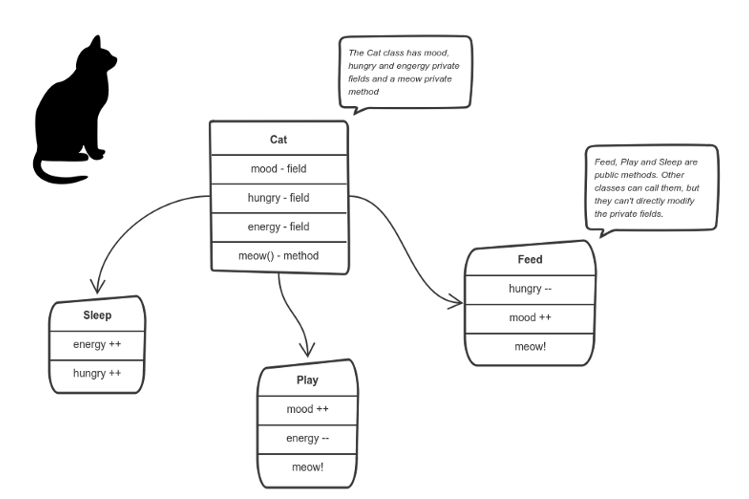

Let’s say we’re building a tiny Sims game. There are people and there is a cat. They communicate with each other. We want to apply encapsulation, so we encapsulate all “cat” logic into a Cat class. It may look like this:

You can feed the cat. But you can’t directly change how hungry the cat is.

Here the “state” of the cat is the private variables mood, hungry and energy. It also has a private method meow(). It can call it whenever it wants, the other classes can’t tell the cat when to meow.

What they can do is defined in the public methods sleep(), play() and feed(). Each of them modifies the internal state somehow and may invoke meow(). Thus, the binding between the private state and public methods is made.

This is encapsulation.

Abstraction

Abstraction can be thought of as a natural extension of encapsulation.

In object-oriented design, programs are often extremely large. And separate objects communicate with each other a lot. So, maintaining a large codebase like this for years — with changes along the way — is difficult.

Abstraction is a concept aiming to ease this problem.

Applying abstraction means that each object should only expose a high-level mechanism for using it.

This mechanism should hide internal implementation details. It should only reveal operations relevant for the other objects.

Think — a coffee machine. It does a lot of stuff and makes quirky noises under the hood. But all you have to do is put in coffee and press a button.

Preferably, this mechanism should be easy to use and should rarely change over time. Think of it as a small set of public methods which any other class can call without “knowing” how they work.

Another real-life example of abstraction?

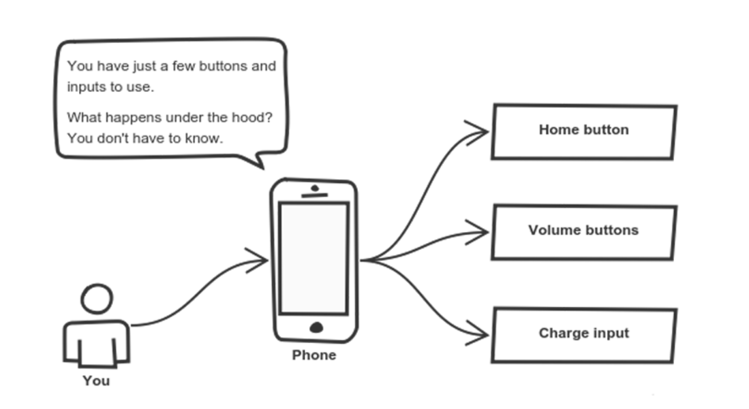

Think about how you use your phone:

Cell phones are complex. But using them is simple.

You interact with your phone by using only a few buttons. What’s going on under the hood? You don’t have to know — implementation details are hidden. You only need to know a short set of actions.

Implementation changes — for example, a software update — rarely affect the abstraction you use.

{In Short, focus on only revealing the necessary details of a System and hiding irrelevant information to minimize its complexity}.

Inheritance

OK, we saw how encapsulation and abstraction can help us develop and maintain a big codebase.

But do you know what is another common problem in OOP design?

Objects are often very similar. They share common logic. But they’re not entirely the same. Ugh…

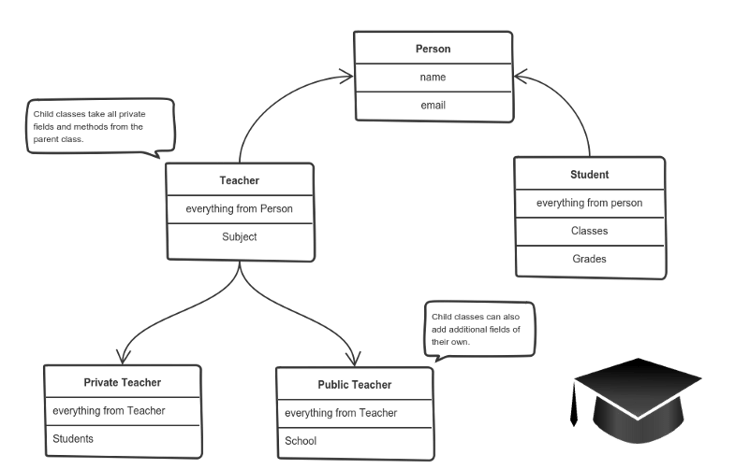

So how do we reuse the common logic and extract the unique logic into a separate class? One way to achieve this is inheritance.

It means that you create a (child) class by deriving from another (parent) class. This way, we form a hierarchy.

The child class reuses all fields and methods of the parent class (common part) and can implement its own (unique part).

For example:

A private teacher is a type of teacher. And any teacher is a type of Person.

If our program needs to manage public and private teachers, but also other types of people like students, we can implement this class hierarchy.

This way, each class adds only what is necessary for it while reusing common logic with the parent classes.

Polymorphism

We’re down to the most complex word! Polymorphism means “many shapes” in Greek.

So we already know the power of inheritance and happily use it. But there comes this problem.

Say we have a parent class and a few child classes which inherit from it. Sometimes we want to use a collection — for example a list — which contains a mix of all these classes. Or we have a method implemented for the parent class — but we’d like to use it for the children, too.

This can be solved by using polymorphism.

Simply put, polymorphism gives a way to use a class exactly like its parent so there’s no confusion with mixing types. But each child class keeps its own methods as they are.

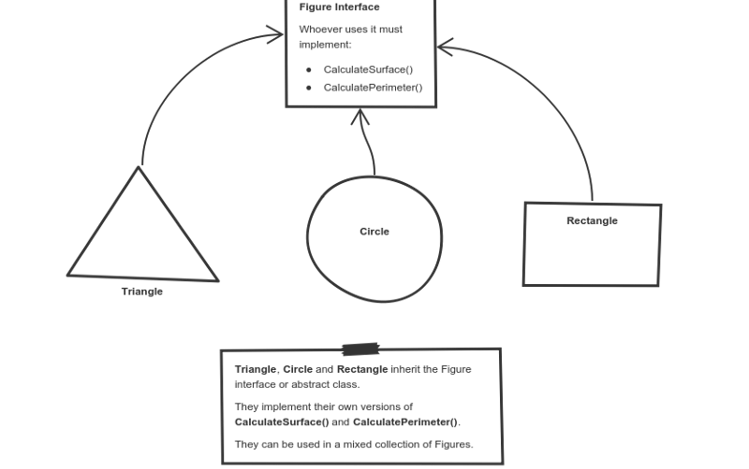

This typically happens by defining a (parent) interface to be reused. It outlines a bunch of common methods. Then, each child class implements its own version of these methods.

Any time a collection (such as a list) or a method expects an instance of the parent (where common methods are outlined), the language takes care of evaluating the right implementation of the common method — regardless of which child is passed.

Take a look at a sketch of geometric figures implementation. They reuse a common interface for calculating surface area and perimeter:

Triangle, Circle, and Rectangle now can be used in the same collection

Having these three figures inheriting the parent Figure Interface lets you create a list of mixed triangles, circles, and rectangles. And treat them like the same type of object.

Then, if this list attempts to calculate the surface for an element, the correct method is found and executed. If the element is a triangle, triangle’s CalculateSurface() is called. If it’s a circle — then circle’s CalculateSurface() is called. And so on.

If you have a function which operates with a figure by using its parameter, you don’t have to define it three times — once for a triangle, a circle, and a rectangle.

You can define it once and accept a Figure as an argument. Whether you pass a triangle, circle or a rectangle — as long as they implement CalculateParamter(), their type doesn’t matter.

Object-oriented Analysis and Design

Object-Oriented Analysis and Design (OOAD) is a way to design software by thinking of everything as objects similar to real-life things. In OOAD, we first understand what the system needs to do, then identify key objects, and finally decide how these objects will work together. This approach helps make software easier to manage, reuse, and grow. It is a software engineering methodology that involves using object-oriented concepts to design and implement software systems. OOAD involves a number of techniques and practices, including object-oriented programming, design patterns, UML diagrams, and use cases.

Below are some important aspects of OOAD:

Object-Oriented Programming: In this the real-world items are represented/mapped as software objects with attributes and methods that relate to their actions.

Design Patterns: Design patterns are used by OOAD to help developers in building software systems that are more efficient and maintainable.

UML Diagrams: UML diagrams are used in OOAD to represent the different components and interactions of a software system.

Use Cases: OOAD uses use cases to help developers understand the requirements of a system and to design software systems that meet those requirements.

UML

Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a visual language that helps developers design, build, and document software systems. UML is a collection of diagrams that represent the structure, behavior, and boundaries of a system and its objects. UML is not a programming language, but tools can be used to generate code from UML diagrams

Design Pattern

Reusable solutions for typical software design challenges are known as design patterns. Expert object-oriented software engineers use these best practices to write more structured, manageable, and scalable code. Design patterns provide a standard terminology and are specific to particular scenarios and problems. Design patterns are not finished code but templates or blueprints only.

Reusability: Patterns can be applied to different projects and problems, saving time and effort in solving similar issues.

Standardization: They provide a shared language and understanding among developers, helping in communication and collaboration.

Efficiency: By using these popular patterns, developers can avoid finding the solution to same recurring problems, which leads to faster development.

Flexibility: Patterns are abstract solutions/templates that can be adapted to fit various scenarios and requirements.

Types of Design Pattern

There are three types of Design Patterns:

Creational Design Pattern

Structural Design Pattern

Behavioral Design Pattern

Inspire

Let's Build the Future

Create

youngcrittersacademy@gmail.com

+1 408-768-1983

© 2024. All rights reserved.